Archives

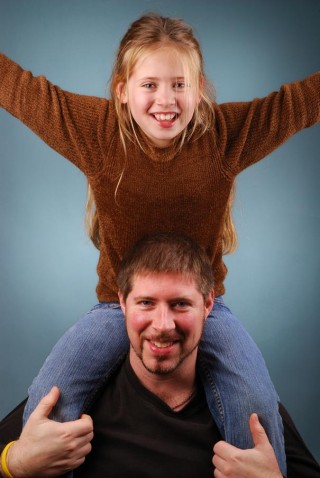

Hungry For Dad

In the second of a two-part series first published in 1999, Peter Walker looked at the role of fathers in women’s eating disorders.

In 1991 Margo Maine wrote (in Father Hunger): “It is time to focus on the positive and crucial role that fathers can play in their daughters’ emerging identity and self-esteem”. And as the 90’s went on, more focus was indeed given to the role of dads and the significance he has in the lives of his children, both negative and positive.

Numerous studies, and books relating to the studies, have emerged, implicating dad in nearly every subtle, and not-so subtle, character flaw, neurosis, and personality and behavioural disorder suffered by adults.

Some positive news emerged too, however. From the shadow of the 80’s supermum the 90’s superdad emerged as a force, putting paid to the notion that dad’s sole purpose is to provide for a child’s material needs.

Dad appears to be a vital component in the complex equation that is childhood.

In the early eighties, many psychologists and research experts dismissed eating disorders as a fad. Maine, however, predicted otherwise, and began to specialise in treating young people with e a t I n g disorders.

She coined the phrase “father hunger” to describe the “natural longing that children have for their fathers, which, when unfulfilled, can lead to a variety of problems”.

This is not to say that every child, especially a girl, who experienced a distant relationship with her father, will develop an eating disorder.

Nor is it to say that every child or adult (eating disorders generally manifest between the ages of 15 and 30) with an eating disorder necessarily had an unfulfilled relationship with dad.

Maine’s study is saying, however, that sufficient evidence exists to suggest that an eating disorder is one problem a child, especially a daughter, might experience as an adolescent and/or adult if the father-child relationship suffers some emotional dysfunction.

A girls’ emerging sexuality can be very threatening to her father. But, according to many studies, and anecdotal evidence, it is Dad who best can help his daughter develop a healthy sexual identity.

Many fathers respond to their daughters’ blossoming sexual personality and changing body, for many reasons, by distancing himself from her, by being less physical, and less emotionally present.

Unable or unwilling to understand and communicate his own feelings to her, she may interpret his sudden withdrawal to mean he cares less for her, that he does not want to be near her any more, or quite simply that he does not love her any more.

Reasons why fathers withdraw from their pubescent daughters can be many. One of the most popular myths about teenage girls is that they need their mothers, not their fathers, during adolescence.

Not true writes Maine.

“Fathers play a particularly special role in their daughters’ passage from childhood to adolescence. Girls need to be “courted” by their fathers, in a non-seductive way, to move from being girls to becoming young women.

They want to feel attractive, womanly, and acceptable to the most important men in their lives (their fathers).This helps them accept their changing bodies and gives them confidence with boys”.

A study out of a Catholic University in Ontario, and reported on in the National Post, claimed that women who perceived their fathers as being warm and supportive have higher self-esteem and are less fearful of intimate relationships.

This is confirmed in other studies. Also suggested in studies, and confirmed by observation and even common sense, girls who grow up without involvement with dad tend to become sexually active at earlier ages, and that girls without fathers tend to look for male approval in relationships before they are emotionally ready.

Girls from fatherless homes are significantly overrepresented in teenage pregnancy statistics.

An environment of fear and suspicion has grown out of the “stranger danger obsession”, reported a British newspaper. It has reached such proportions that many fathers are afraid to be too physically affectionate with their children, and especially their daughters.

This fear is often heightened when parents are separated and access/custody arguments make allegations of inappropriate sexual behaviour an easy and powerful weapon mothers and lawyers can use.

It is no wonder many dads keep just that little guarded with their daughters, both physically and emotionally, distance which girls can interpret as rejection. When this happens, girls, writes Maine, “often experience self‑doubt, self-deprecation, and depression”.

“They may act out their distress in different ways – by withdrawing from social contact, by being promiscuous, or by the self-loathing and rejection of self that is expressed through an eating disorder”.

Fathers need to be aware of the issues facing their daughters. Many little girls, suggests Maine, respond to messages in the media aimed at them “by becoming preoccupied with their appearance or by dressing in a provocative or adult style”.

Instead of feeling overwhelmed by this (often) premature sexuality, fathers “should find ways to remain close to their daughters as the girls experiment with these behaviours”.

In the second half of this century, women roles have expanded and they have become more able to pursue professions, interests, and lifestyles that their mothers couldn’t.

“These revolutionary changes have contributed to inner turmoil and self-doubt, which in turn are being conveyed to today’s little girls and adolescents”.

“Obsession with physical appearance and weight have become the primary means of dealing with this anxiety”.

Girls easily become victims of the “If only I were thin” fantasy, a myth the multi-billion dollar diet, exercise, cosmetics, and plastic surgery industries are only too willing to cash in on.

“A father’s positive messages,” continues Maine, “can help his daughter face doubts she may have about what being a woman means today.

He can help his daughter discern her life’s direction, values, and identity.” And further, ‘When dad’s role in the family is a constructive one, the daughter will not have to rely on the “If only I had a perfect body” fantasies in order to feel competent and successful as a woman and comfortable with her femininity”.

Of families, Maine says “father hunger is a cultural tradition handed down from one generation to the next … (many) men and women enter parenting with a handicap that even they may not recognise … How can a man who was not fathered know how to parent? … Few couples have been able to overcome the impact of father hunger in their parenting.

Instead, most families adjust and live a life of functional dysfunction.

Mothers tend to do too much to compensate for their husbands’ absence. As wives, they feel overburdened and overextended and need help from their husbands, but their background of father deprivation keeps them from asking; they feel they have no right to request more from men.

Men continue to feel isolated and unimportant to the family . . . Each parent may want more from the other but doesn’t know how to ask … this leads to bitterness and hostility.

This is the template young women are given for their lives. They feel guilty and resentful, and, says Maine, “wanting more from dad and being angry with (mum) easily translates itself into food conflicts”.

Many women, both in Maine’s America and here in New Zealand, can trace an eating disorder to a family dysfunction as described above. For many, an eating disorder is one way an adolescent girl can feel some kind of control over her desperate, lonely situation.

Said one girl quoted by Maine: “My anorexia was a challenge to my father, to get him more involved.” This sentiment has been expressed by many New Zealand women, too.

It is too simplistic to suggest that family dysfunction will necessarily cause an eating disorder in an adolescent girl. It is not too simplistic, however, to suggest that fathers play a crucial role in the development of their daughters’ self-image.

Maine offers several ways for men to develop a nurturing and loving relationship with their daughters. Look critically and honestly at your relationship with her mother.

Accept, and convey, that you have flaws (“this will help [your daughter] overcome the constant struggles for perfectionism that her eating and body image problems reflect”).

If you are separated or divorced, “own some of the blame for the breakdown of the marriage so that your daughter does not feel that the responsibility for relationships belongs only to women”.

Consider the “role” you play in the family. The “King of the castle” model in which dad rules autocratically from a distance, or even absence, showing up only to discipline, is not conducive to loving and nurturing.

Look at your own losses and wounds, and how they prevent you from connecting with your daughter.

Listen.

The greatest challenge for dads is to constantly redefine the fatherhood role as their daughters grow. What your daughter needs at five is different from what she needs at ten, and at fifteen.

It is your responsibility to figure out what she needs and provide it in a context promoting acceptance, tolerance, and love.

Next: The Mother Myth