Engaging Dads Better

Engaging dads has become a hot topic amongst providers of family services, with more and more considering this a key issue for the quality of their services.

Harald Breiding-Buss writes that in order to involve dads in the right way, service agencies need to involve them for the right reasons.

When you ask people about why they think engaging dads is important for people who work with families, the answer you usually get is along the lines of: because dads are good for kids, or: because parenting has become too female-focused.

There is a much more compelling reason, however: dads spend a lot of time with their children alone. Some children are completely dependent on their fathers, like the babies in our Dependent on Dad study, while others may see little of their dad, but almost all of them would have some times where there is only dad, even if it is only because mum has gone out shopping.

Another intriguing aspect of the Dependent on Dad study was that sometimes it was exactly the men with the troubled backgrounds who would end up sole-caring for their children—fathers that a midwife or similar person may well have ’written off’ in her mind. The message from this is: you simply cannot know how the child you are visiting today is being cared for tomorrow. By not including dads, children are in danger of becoming disconnected from important social services, because their fathers are.

Another intriguing aspect of the Dependent on Dad study was that sometimes it was exactly the men with the troubled backgrounds who would end up sole-caring for their children—fathers that a midwife or similar person may well have ’written off’ in her mind. The message from this is: you simply cannot know how the child you are visiting today is being cared for tomorrow. By not including dads, children are in danger of becoming disconnected from important social services, because their fathers are.

So while it is very important to reach out to solo dads, it is even more important to reach out to all dads, exactly because any one of them may become a solo dad in the future.

Much has been said and written about the failure of our family organisations to effectively include fathers, but our study indicates that, in fact, there isn’t

anything wrong with how a given service is delivered. Not one of the dads we interviewed complained about being looked after by a female, for example, and more often than not the more intensive support services were given a 10 out of 10 by those dads who were actually enrolled in them. The only difficulty is actually getting enrolled.

This is where it is so crucial that a father has been engaged while he was either still together with the mother, or already separated but not yet the full carer of the child. This not only increases the likelihood that the father will actively seek support in the future, but it gives him a foundation in parenting and, importantly, some tools for coping with the stress issues that single parents face more than the partnered kind. Too often family workers assume that only the ‘primary caregivers’ have to deal with these.

Fathers’ and men’s groups have long advocated to have male staff dealing with male clients, but there is no hard evidence that this actually makes any difference.

What is needed is organisations who can successfully role model cooperation between men and women. All organisations providing family work should have a mix of competent male and female staff, and neither sex should work exclusively only with their own. As long as male workers are employed to work only with males there will be a ‘problem’ stigma attached to male parenting, and females will continue to be viewed as the only sex actually competent in parenting issues.

But even if such a mix of male and female frontline workers is not achievable in the short term, organisations can make a big difference for families if they promote their service to both parents. The key phrase here is: Expectation, Expectation, Expectation.

While written promotional material, web sites etc about a service is important, the scene for a service’s involvement is set on that very first personal contact. This is where a family worker has the choice of asking for an appointment with both parents, or only one of them.

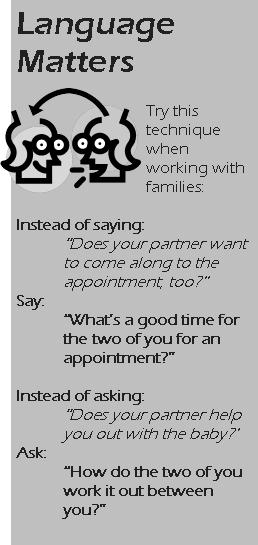

This initial approach is very important. Let’s say a midwife phones a family to make an appointment for a Well Child health check, and the baby’s mother answers the phone. The midwife can now make an appointment with her and say that it would be good if her partner would also be present. Or she could, from the start, ask what time would suit both of them (and, of course, baby).

The expectation created with the first scenario is: this is a service for mum and baby, where dad is also allowed to be. The second scenario creates a different expectation: it conveys that this is a service for the family. The midwife coveys that she expects to find both Mum and Dad at the appointment, and that it is up to the couple to decide otherwise, whereas in the first scenario Dad’s attendance is optional.

The same thing also works for families where there are other significant people that should be included, such as the mother’s mother or other people from either parents’ whanau. However, involving other people should never be at the expense of involving the father. Fathers and mothers are generally the only legal guardians when a child is born, and have unique responsibilities as well as rights under both national and international law. When things go ‘wrong’ with the mother, the father is more likely than any other family or whanau member (including the mother’s mother) to take over primary responsibility for the care of his children.

Where parents do not live together, and the child lives mainly with the mother, it can get tricky for a family service. To err on the side of caution the father should be involved and informed. Under the Guardianship Act, both parents have the right to full access to any information there is about the child. Services should be proactive in giving non-resident fathers this information and not wait for him to put in an official request under the Privacy Act.

The most common reason why this so often does not happen is because the mother of the child does not want it to happen. Sometimes this is out of fear that such information would give the father ‘ammunition’ in a current disagreement about day-to-day care. This creates a loyalty conflict with a family worker: to work effectively with this mother and establish a relationship of Trust would require to work with her and only her. But to meet the legal rights of the child and its likely present and future needs, the father should be given information about the service and the child.

Many family workers have been solo mothers themselves and therefore may identify strongly with the situation of the mother. This, of course, can lead to the worker being perceived as ‘siding’ with the mother and the father getting the impression that he is facing a battlefront over the mere issue of maintaining a relationship with his child.

Again, expectations are the key. When a first child is born it is rare even for separated parents to start fighting about the care of the baby immediately. This is a window of opportunity, and involving both parents in the service at this point in time sends a very strong signal of an expectation for cooperation.

When a child is a bit older and the damage has already been done (i.e. an expectation has been created of the mother being in sole charge of the child) this becomes much more difficult, and at times a family worker really has no choice but to work with only one parent in order to make any positive difference in the child’s life.

However the service’s management needs to try to mitigate such situations as much as possible to protect the child’s rights. If, for example, a family worker has strong negative opinions about one of the parents, or disagrees with applying the law or organisational policies in a specific case, there are management tools to resolve this: supervision is not the least important of them. It is also important that the organisation allows non-resident parents to complain so that it is able to gauge whether it has a problem with its internal culture.

The good news is that over the last few years I have noticed more and more discussions about these nitty-gritty issues of father involvement pop up within organisations. Research on this is still far and few between, and what is needed are some good pilot studies accompanied by sound external evaluation that try out alternative ways of working with families so that both parents are included by default.

Next: Supporting Breastfeeding