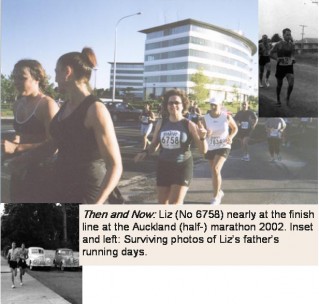

Running Like Dad

When Liz Oakes set herself the challenge of completing a half marathon it was memories of her father and his passion for running that kept her going.

My commitment to running has always wavered. I’ve spent more time watching long-limbed athletes as they glide across the pavement, than running myself. In contrast, my own solid, muscular legs hit the concrete in staccato-like thuds. My attitude changed when I took up the challenge to run a Half Marathon.

Over twelve weeks I ran four times a week. I trained day and night, on the beach, through the bush, on the suburban streets, in the sun and the rain. Alone, apart from some jingle bomb bouncing in my head, I often felt like giving up. The isolation of endurance training pushed me beyond any experience where I’d had to rely on will-power alone. It was in this space my thoughts often turned to my father and it was his memory that gave me the strength to keep going.

Dad liked to run. In the 60s and early 70s, before it was popular, he’d come home from his job as a haberdashery salesman, put on his trainers and disappear into the twilight. A lone figure bobbed up and down on the horizon. He belonged to the Lyndale Running Club. As a preschooler I was signed up with the East Coast Bays Running Club and later with Takapuna. At age nine I won every running race in our school sports day. Dad was there and I was proud. He signed me up for winter training. I went twice. My running achievements were more to do with good genes than good training.

My strongest childhood memory is at age four. I’m standing at my parents’ bedroom window watching my Dad pack his bags into the boot of his car. I couldn’t understand why he was leaving. It looked like he was running away.

Dad became a Sunday and Thursday night running club Dad. On the weekends he would take me to the beach, the movies, the museum, the Easter show. We shared a sweet tooth and there was always as much ice cream and lollies as I wanted. Throughout his life Dad had three heart operations and slowly over the years his running slipped away.

I remember when I was eight, Dad taking me to watch the summer track and field events at Mt Smart Stadium. The smell of hotdogs and freshly mown grass lingered in the air. Riding down the hill towards the stadium on a piece of old cardboard, I would yell and scream to the athletes with almost hysterical enthusiasm. Later when I was on my OE he wrote and told me of how he was a track and field volunteer at Mt Smart for the 1990 Commonwealth Games. He passed away 18 months after his third heart operation.

If I could wave a magic wand, I’d put myself in one of those “Back to the Future” movies and go back and find Dad. I’d sit on his knee, he would tell me that I was pretty and that he loved me. I’d say, “I love you too Dad.” Looking back, I realise he often seemed awkward, like he didn’t know where to put himself. I don’t think loving words or public displays of affection were his language. Or perhaps it was because he had never experienced it himself.

I stood, surrounded by thousands of runners, at the start line to the Auckland Marathon. All my senses were fully heightened; I was switched on and ready to go. The starter’s gun exploded. The bunched crowd crawled, walked and finally scattered as we were off to a run. It was a crisp and bright morning, a fantastic day for a run. As I ascended the top of the Harbour Bridge, I let out a “Yahoo!”.

I finished my Half Marathon in just over two hours. It was a life-changing and liberating experience. On those long hard training runs, as I was calling out for some strength to get me through, it was then that I saw him. In my mind’s eye, I would see this curly-haired, olive-skinned, 30-something man, just like in his old black and white running photos. He was running up ahead, beckoning me to come on, to keep going. He moved so freely, so at ease within his own skin. He wasn’t running away from me and I knew I would make it to the finish line.

Next: Family Politics